Why do we tax corporations?

by Scott Dyreng, Tax Policy Network and Senior Associate Dean for Innovation and Professor of Accounting at the Fuqua School of Business at Duke University

Ask ten people why corporations should pay taxes and you will hear three answers again and again.

- They have a lot of money.

- They use public infrastructure.

- They control too many resources and have too much power.

Those answers are satisfying at first glance, but if you hang your hat on one of those pegs, you’ll likely wish you had chosen a more robust hook. To understand why, we need to dig into a few fundamental issues related to corporate taxation.

What is a corporation and does it pay taxes?

Jensen and Meckling (1976) described a corporation as a “nexus of contracts.” Workers agree to work, investors agree to provide capital, suppliers agree to deliver inputs, customers agree to purchase, and the corporation is the structure that makes all of this easier to coordinate.

So, when we say, “the corporation pays the tax,” we need to be more precise. Though the corporation might indeed pay the tax by writing a check to the government, what matters is who bears the economic burden of the tax. The economic burden is always borne by humans. In the context of a corporation, the economic burden will fall on one or more of the following groups of humans: investors through lower returns, workers through lower wages, or customers through higher prices. Research generally finds the burden is shared, not dumped entirely on one group (e.g., Suarez Serrato and Zidar, 2016).

Three weak reasons to tax corporations

Weak Reason 1: “They have a lot of money”

This argument essentially ignores a fundamental question: whose money is it, really?

Yes, many corporations have large bank accounts. But if a corporate income tax leads to wage reduction or price hikes to cover that tax bill, then the corporate income tax is akin to directly increasing taxes on workers or consumers. Likewise, if investors end up with lower returns, then the tax is not so different from taxing the investor directly. A corporate income tax, therefore, runs the risk that it is not ultimately borne by someone with “a lot of money.” Instead, it might be borne ultimately by those who can least afford it, like rank-and-file workers or consumers.

If one desires to “tax the rich,” it isn’t obvious that a corporate tax is the best way to get there.

Weak Reason 2: “They use infrastructure”

Corporations use roads, water, and sewage services. They have legal standing in our courts, benefit from our national defense, reap gains from workers who were educated in public schools, and so on. But all these benefits accrue to humans, not to this nexus of contracts we call the corporation. Indeed, in much the same way that the economic burden of a tax can only be borne by humans, the benefits of the public goods that corporations use can also only accrue to humans.

Many public goods are not funded by income taxes, but by other taxes corporations pay even if they don’t pay any income tax at all. Fuel taxes help fund roads, and corporations pay fuel taxes. Property taxes help fund schools, and corporations pay property taxes. The idea that one should “pay for what is used” works best when the tax base is tied to the use. Corporate income often has little connection to actual infrastructure use. A firm can be unprofitable and still use a lot of public goods, or be highly profitable without using much physical infrastructure at all.

If the real beneficiaries of public goods are ultimately shareholders, workers, and customers, one can tax those people directly rather than pretending the corporation is the final consumer of a road.

Weak reason 3: “They control resources and have too much power”

This argument is closer to a real concern. Large corporations can influence politics and society. However, a tax on profits is a blunt way to fix a power problem. If one is concerned about monopoly power, the better tool is antitrust. If one is concerned about lobbying and political influence, the better tools are transparency rules and campaign finance law. If one is concerned about environmental harm, the better tools are carbon taxes and environmental regulation.

A corporate income tax might reduce corporate resources, but it is not well targeted to the specific problem of power. It is like knocking on the wall to find a stud before hanging the hook for your hat. A more precise tool, like a stud finder, will greatly increase the probability that the nail actually hits its mark.

Three stronger reasons to tax corporations

Strong reason 1: It is efficient to collect

Sometimes the best policy reasons are the most obvious. The first is simply logistical.

Sending one tax bill to a corporation can be far simpler than sending millions of complicated, individualized bills to shareholders. The latter would require complex allocations of profits across huge numbers of investors, which in turn would create a larger, more complex administrative burden.

We already do this kind of thing in other parts of the tax system. Flow-through entities pass all profits to owners, and the owners pay tax through the personal tax system. Retailers remit sales taxes because it is administratively easier than having every customer mail in their own sales tax. The corporate income tax is another place where the corporation is used as a collection point because it is practical.

Strong reason 2: It helps reach foreign investors

Ownership of U.S. companies is global. If foreign investors earn returns through U.S. businesses, it can be difficult to tax that income through the personal tax system, because those investors may not live in the US or file taxes in the US. Taxing the corporation can indirectly tax some of that foreign-owned income.

This is not about punishing foreigners. It is about making the tax system workable in a world where capital crosses borders quickly and fluidly.

Strong reason 3: It gives the government a window into business operations

A corporate income tax requires measuring profits and documenting the inputs behind those numbers. This reporting gives the government a legal reason to examine corporate financial results, which can provide oversight and influence behavior at the margin.

Even if you set a low tax rate, the reporting system itself creates a form of visibility. It is a window, not a spotlight, but it matters.

The big reality check: corporate income taxes are a modest slice of revenue

People talk about corporate taxes as if they are the key to funding the government. The numbers suggest otherwise.

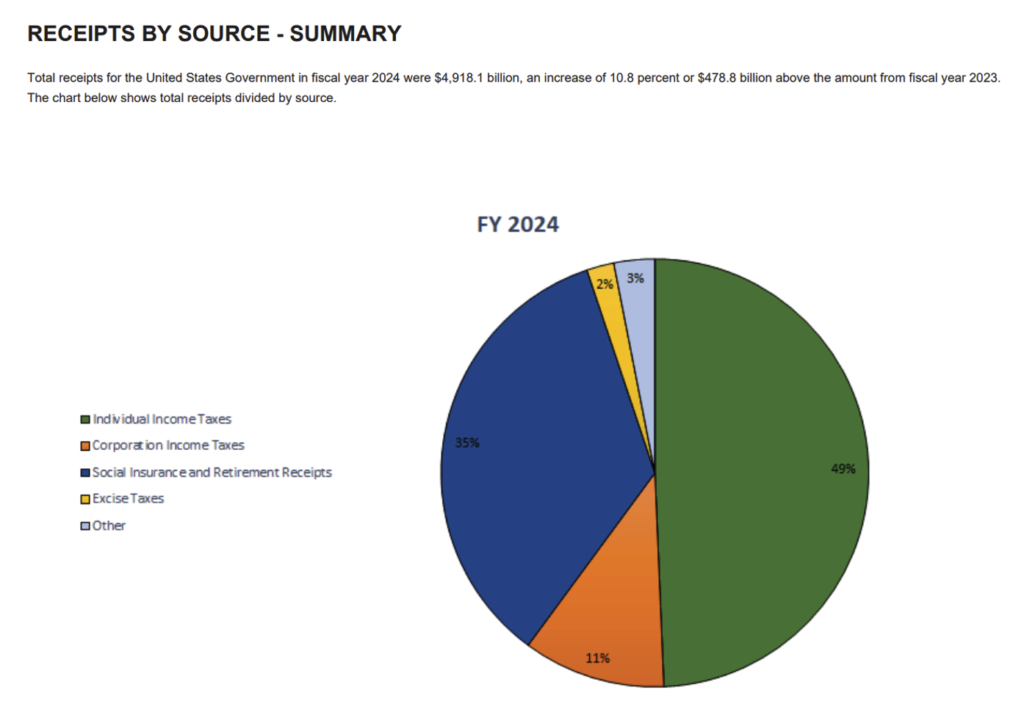

In fiscal year 2024, total federal receipts were about $4.918 trillion. Corporate income taxes were about $529.9 billion, which is roughly 10.8% of total federal receipts. Individual income taxes and payroll taxes were far larger.

Here is a figure showing the breakdown:

It is tempting to look at that 10.8% figure and conclude, “Aha, corporations must be cheating.”

Tax avoidance exists, but it does not explain the basic arithmetic. The IRS’s own tax gap projections for tax year 2022 estimated the corporate tax gap at about $50 billion. (irs.gov) Put that next to roughly $530 billion in annual corporate income tax receipts and roughly $4.9 trillion in total federal receipts, and you get the scale: closing the entire corporate tax gap would increase total receipts by about 1%.

It also does not come close to fixing the deficit problem. The federal budget deficit in fiscal year 2024 was about $1.8 trillion (Congressional Budget Office). Even if corporate noncompliance fell to zero overnight, an extra $50 billion would cover only a small fraction of that gap.

So yes, enforcement matters. But the low share of revenue from corporate income taxes is mostly about the structure of the tax system and the size of other revenue sources, not about a hidden stash of corporate money that could single-handedly solve the nation’s fiscal challenges.

Conclusion

Taxing corporations because they “have money,” “use roads,” or “control everything” makes for great slogans, but weak policy. A corporation is a legal structure connecting people, and the burden of corporate taxes ultimately lands on people in messy, shared ways.

The better reasons to tax corporations are practical and institutional: corporate taxes are an efficient collection mechanism, they help reach foreign investors, and they give the government a legitimate window into large businesses operating within its borders.

Corporate income taxes are a meaningful slice of revenue, but not a dominant one. Even perfect compliance would not turn them into a fiscal magic wand.

Scott Dyreng is the Senior Associate Dean for Innovation and Professor of Accounting at the Fuqua School of Business at Duke University.