Equipping Teens to Give Health Misinformation A Miss in Bihar, India

By Simon Chauchard and Sumitra Badrinathan

Key challenges facing our society require individuals—in their personal, professional, and policymaking roles—to engage in science-based decision-making. Navigating the information environment around health can be challenging—adolescents face particular challenges when encountering misleading information. This includes navigating media, peer groups, and family opinions to, ultimately, take, trust, and promote evidence-informed protective health behaviors. Such behaviors can be obscured by inaccurate and misleading information.

Living in a low-income and low-literacy environment, with its lower levels of state capacity, can create and compound a favorable ecosystem for the dissemination of unproven information. For example, imagine you are Jyoti, a teenage girl in a village in Bihar, India, near the border with Nepal. You live with your parents and two brothers in a house that has electricity. Some of your neighbors have a radio or a TV but your household does not. One of your relatives likely owns a cell phone, though it may not be a smartphone, or it may not have sufficient data for everyone in the household to access the internet. Bihar is the poorest state in India and this is reflected in your own household’s annual income: US$1,500.

One day at school, one of Jyoti’s friends tells her she has been coughing up blood and feeling feverish— both known symptoms of severe dengue. What should the two friends and their parents do? Who should examine the friend? One common belief in this rural Bihar is that consuming papaya leaf extract can increase one’s platelet count and help speed recovery. While neither understands the mechanisms through which papaya leaves may act, this belief may lead Jyoti and her friend to dangerously underreact: The clinical impact of consuming papaya leaves is indeed generally disputed; more importantly, the severity of the situation would instead require a different type of attention, ideally from a trained medical professional.

As part of the SSRC’s Mercury Project Research Consortium, we collaborated with 17 other research teams around the world to conduct solutions-oriented research to address challenges like Jyoti’s: How to effectively and efficiently help people avoid and resist low-quality health information. By doing so, they can act to protect their health. To enable this, we need to build information environments that support science-based health decision-making, such as vaccination. The challenges of inaccurate and overwhelming information—an infodemic—has been highlighted by researchers and policy actors.

But in a context like rural Bihar, people like Jyoti live in a partly analog information environment, with most relying entirely on offline information spread by word-of-mouth. Our understanding of this environment has been shaped by our previous research experience as well as engagement with government and NGO stakeholders. We’ve had to think about misinformation and protective education differently. Intervening on adolescents presents a prime opportunity to move the needle: adolescents likely have more malleable attitudes and behaviors. This may overcome a challenge encountered in misinformation studies: motivated reasoning, our tendency as humans to resist correct information if it goes against our prior beliefs, can sink media and information literacy training.

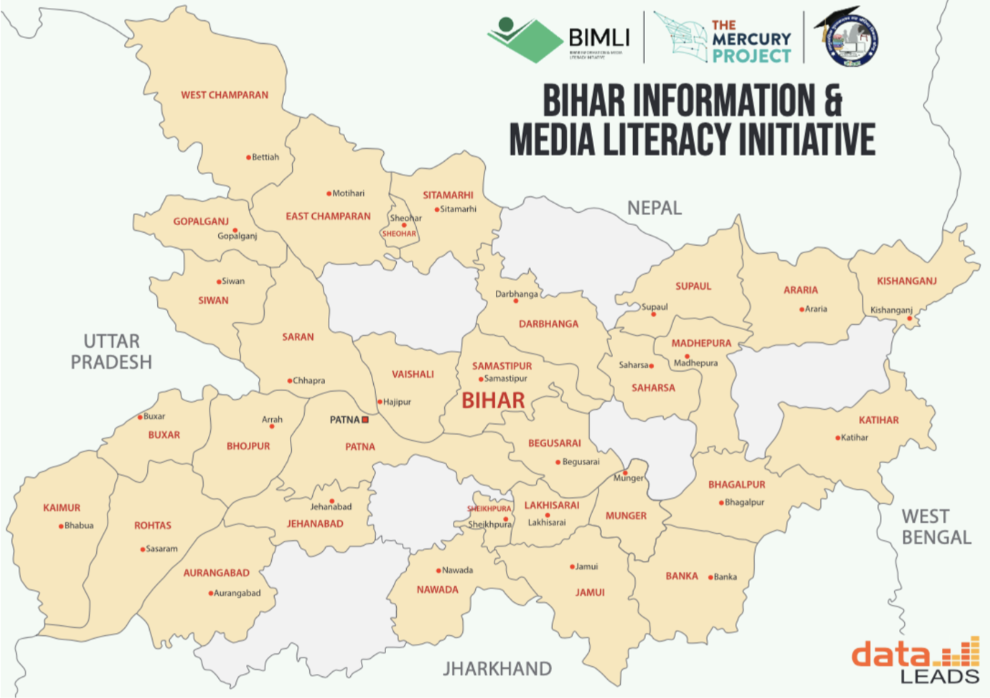

Here, through Jyoti’s experience, we will examine the health information environment in rural Bihar and her interaction with a new initiative, the Bihar Information and Media Literacy Initiative (BIMLI). We’ll explore:

- Why media and information literacy training is promising—and how much we don’t know;

- the careful development of a fit-for-context, three-month curriculum for teens in rural Bihar in partnership with DataLEADS and the Bihar Rural Livelihoods Promotion Society (a government entity also known as JEEViKA);

- how, starting on January 30, 2024, we are executing the largest evaluation of media and information literacy training to date in the social sciences that we’re aware of, reaching over 14,000 students aged 14–18 across 600 villages; and

- the promise and importance of measuring the impact of what happens when teenagers like Jyoti go home with new information and new skills to drive policy decisions

Media and information literacy training as protection against misinformation

Literacy in Jyoti’s village mirrors that of the state: about 60 percent of people can read. Because internet penetration remains low and few people own TVs, information spreads mostly by word-of-mouth, coming in from those who have migrated for work as well as from newspapers and occasionally radio. In addition, state capacity is weak; people tend to rely on informal networks rather than official sources for news and information. To navigate this information environment, Jyoti needs key skills in information literacy and critical thinking to assess the accuracy of information she encounters—from elders and those with local authority—and decide how to act on it. For example, in the case of dengue, Jyoti’s friend would likely require fluids, rest, and to manage her fever and pain with acetaminophen. How can they come to this decision?

Jyoti needs key skills in information literacy and critical thinking to reduce vulnerability to falsehoods or misleading information. She also needs information about who to trust in this situation, and about what makes a good source. Information disorder scholars increasingly note the best defense against inaccurate and misleading information is offense: preparing in advance for exposure to misinformation. Why? Several common approaches to reducing the consumption of low-quality information—such as fact-checks, warnings, and corrections—are top-down and reactive. These reactive tactics have limited long-term effects and occasionally produce backlashes.

Leaders around the world are expressing growing interest in how to build protective literacy skills in adolescents; the question is how. The governor of the US state of New Jersey, for example, in January 2023 signed a bill requiring media literacy training for children from kindergarten through 12th grade. In India, plenty of people are worried about kids like Jyoti as they navigate their information environment to make health decisions. The need to combat misinformation has sparked initiatives by governments, NGOs, and civil society organizations to provide media and information literacy training to the public. In Finland, this has taken the form of making media literacy core to the whole school curriculum, starting in pre-school. But in almost every other case, media and information literacy interventions are one-shot, whether delivered as a drop-in session by an NGO or brief in-person training. Most existing programs are oriented toward kids with digital literacy skills who are already regularly accessing the internet.

Crafting a context-specific curriculum to build media and information literacy skills with teens in Bihar

With our partners, we set out to deliver a robust and grassroots media literacy curriculum that works for teens in Bihar. With DataLEADS, we drew on existing media and literacy (MIL) efforts to develop the strongest possible way to boost (health) information literacy in Bihar. For us, this needed to be (1) face-to-face, (2) multi-session, (3) facilitate on-going discussion between teachers and students, and (4) have government or official backing. Furthermore, we needed to break down abstract concepts in a way teens could process them and then use repetition, iteration, and community-building to make them stick.

With the principles of iteration, dialogue, and concreteness in mind, we designed a three-month program to help youth like Jyoti improve how they consume and react to health and other news. The curriculum includes four training sessions, with modules focusing on (1) vaccination, (2) psychological biases to misinformation, (3) trusting authority sources, and (4) talking to family members about misinformation. Additionally, students have homework between sessions and take part in several participatory field exercises, guaranteeing the experience extends beyond the classroom.

Building a new curriculum takes teamwork to get the details right. Translating key concepts into colloquial Hindi was hard enough; indeed, we found few translations of these ideas beyond English. But getting the words right was not enough; we had to make it practical, at the level a teenager can understand. In many existing media literacy classes, there is an emphasis on giving theoretical definitions to ideas like critical thinking and critical reading. But what can teens do with theory? With DataLEADS at the helm, through iteration with our trainers-of-trainers in September and October 2023, we worked to make concepts digestible for a 14-year-old like Jyoti, leveraging local examples, such as the need to talk to elders. For example, trainers would explain that when you read a text, you have to question not just the original source of the information but also the transmitter, since so much of information sharing in India is through word-of-mouth and informal neighborhood conversations. Furthermore, translating the content of the curriculum to be engaging for teenagers meant that we adapted many of the examples to hands-on exercises, such as a role playing task in the classroom where students discussed the importance of vaccines with an older relative.

Delivering a new curriculum also takes teamwork. Working with DataLEADS means youth like Jyoti are participating in classes delivered by one of the world’s leading organizations in media and information literacy training. Working with JEEViKA means that these classes are being held in public Community Library and Career Development Centers across rural Bihar, with the support of a major state-level agency.

Designed to build cumulative knowledge and skills across sessions, BIMLI offers a more intensive experience than virtually all existing media literacy interventions, maximizing the likelihood of its beneficial effects. We believe it has the potential to work. But we need to test it to be sure.

Evaluating BIMLI in Bihar: If it can make it here, it can make it anywhere

Across income brackets, we lack clear evidence on whether media and information literacy training can successfully and cost-effectively change behaviors—not just attitudes. While teaching youth critical-thinking skills is an attractive solution, such efforts are often expensive, and we do not know if they work or are worth the given scarce resources. But if we can show some results in a challenging context like Bihar, and in a challenging population like teens, there’s a good chance it could be done in other places, too.

To understand how best to allocate resources to support protective health behaviors, we need rigorous empirical evidence of whether, how, by how much, for whom, and for how much such training can lead to changes in behaviors like vaccination. To do this, we have launched a large-scale randomized controlled trial across 600 villages in 30 (of 38) districts in Bihar. This means about 14,000 students are part of our study, with about 7,000 of them receiving the BIMLI curriculum, and another 7,000 with highly valued training in conversational English. We randomly assigned 300 villages to BIMLI and 300 to English; we don’t believe that training in English will affect our key outcomes of interest, such as the ability to discern truth from falsehoods or vaccination behavior.

Because of the random assignment, we will be able to make causal estimates about the efficacy of the BIMLI curriculum. That is, we’ll be able to say whether a teen like Jyoti who participated in BIMLI can distinguish true from false statements at a higher rate than a nearly identical teen who participated in conversational English. Because of the randomized study design, any improvement in outcomes we care about—better ability to discern false from true, trusting authority sources, increasing reliance on vaccines—can be attributed to BIMLI. This is because the other potential explanatory factors, such as prior beliefs about medicine or one’s political affiliation, are the same in areas receiving the BIMLI intervention and those receiving conversational English; the key variation is what set of lessons they receive. However, there is more we would like to know about how the program affects Jyoti and her household, including over time.

Boosting BIMLI: Understanding what Jyoti takes home

A key question we are not equipped—yet—to answer is whether Jyoti will be willing and able to share what she has learned with her family and whether, in turn, they gain new skills and undertake new health behaviors. We think it is likely that this will happen. If it does, it makes a stronger case for adopting programs like BIMLI, which are extensive and labor-intensive. So too would understanding how long new skills and behaviors stick with teens and with what consequences. The BIMLI team welcomes new partnerships to this end.

After participating in BIMLI, what do we hope will be true for how Jyoti engages with information—and misinformation? First, the intervention should increase her awareness of misinformation, highlight its potential dangers, as well as enhance her understanding of the various psychological mechanisms that allow this misinformation to spread. While it may seem minimal, and a direct effect of having been exposed to the class material, this increased awareness could, by itself, lead to important norm-shifting in how students such as Jyoti, around them, consume information. Given the theory, teamwork, and pragmatism we put into building BIMLI with DataLEADS and JEEViKA, our hope is that this would also lead to broader changes in attitudes and/or behaviors. Provided students are able to access reliable information and to check a variety of sources as they grow up, the program may shift their media diets, help them be more discerning in how they process or share information, and/or assess sources. It may additionally further motivate them to engage with anti-misinformation efforts, or to join such grassroots efforts when crises occur.

Even the best-designed solutions need to be tested in the real world before scarce government resources are invested. We are keenly awaiting our results, which we expect by June 2024, to confirm whether these outcomes were impacted, at six months, by participation in the BIMLI training, and which subgroups of participants can be best counted on in years to come to help keep misinformation from blocking protective health behaviors.

Writing and editorial support for this article provided by Rodrigo Ugarte, Jeff Mosenkis and Heather Lanthorn.

Simon Chauchard is Associate Professor of Political Science and Distinguished Researcher (Investigador Distinguido) at the University Carlos III (Madrid), a member of the Institute Carlos III Juan March (IC3JM), and the PI of the POLARCHATS ERC project. He also coordinates the activities of the PIMlab, the hub for political behavior research on Polarization, Identity and Misinformation within the IC3JM and within the department of social sciences at UC3M.. He previously held positions at Dartmouth College, Columbia University (SIPA) and Leiden University. He is a current Mercury Project grantee; much of his current research, including the BIMLI project, focuses on the causes and consequences of social media misinformation in developing countries.

Sumitra Badrinathan an assistant professor of political science at American University’s School of International Service. She was a postdoc fellow at the University of Oxford’s Reuters Institute (2021-22) and received her Ph.D. in Political Science from the University of Pennsylvania in May 2021. Her research focuses on political communication in South Asia, with an emphasis on new platforms like WhatsApp and their effects on political misinformation, media trust, and the quality of democracy. I use experimental and survey methods to investigate potential solutions to misinformation in developing countries along with the consequences of misinformation on political and societal outcomes, including violence, vote choice, polarization, and social cohesion. She is a current Mercury Project grantee on the BIMLI project.

Related Programs

Related Programs