As Maya Chandrasekaran approached the final challenge of her public policy/economics PhD, namely deciding what to do next, an unusual job listing caught her eye. “It wasn’t your typical postdoc, but it looked like it had been written for me,” Chandrasekaran, the inaugural SSRC Presidential Fellow, explained. “Oftentimes, really great research just stays in the research world, but this was about building a policy accelerator to speed up how research makes change in the world. It was exactly what I wanted to do.”

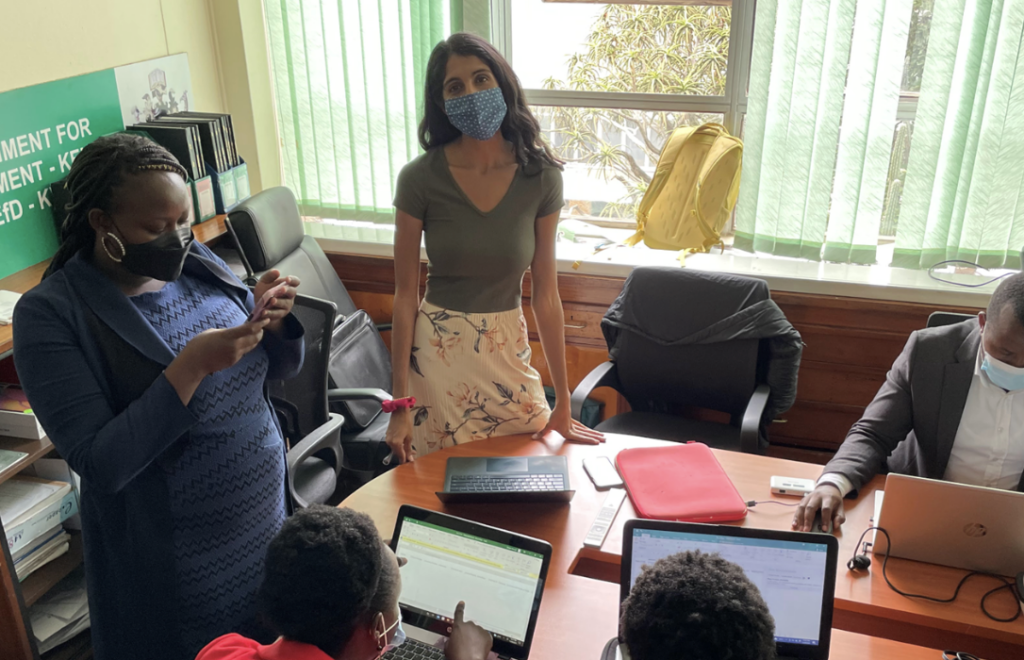

Chandrasekaran’s own work measures the impacts of potentially helpful programs, including programs that increase access to safe and reliable water, sanitation, and hygiene and improved cookstoves, clean fuels, and electricity in low- and middle-income countries. She hopes to help the Council expand its portfolio of work supporting the research-to-policy pipeline. “One thing I saw in my work, studying women’s use of healthier and more environmentally friendly cookstoves across East and Southern Africa, was that in many other countries, there’s been wonderful growth over time in the partnerships between governments and research networks to design and test policies. We’d like to see more of that in the US.” She points to organizations such as MIT’s Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab (J-PAL) and the University of Chicago’s Crime Lab as examples of research organizations that have been both producing new scientific evidence and helping governmental agencies implement evidence-based interventions. “J-PAL’s work with researchers and governments has had a big influence in countries like India, Peru, and Kenya. And in Chicago, the Crime Lab has tested programs like Becoming a Man, teaching young men how to use tools from cognitive and behavioral science to stop violent behavior. The researchers found it reduced arrests for violent crimes and increased high school graduation rates by impressive amounts.”

But in surveying the growth of these kinds of impact-oriented research partnerships, she points out that it’s typically the better-resourced universities that have the infrastructure needed to run complicated, real-world research in partnership with governments or other organizations. “I saw this in my own training at Duke—I came into a system that had everything I already needed to be successful. We had people who could help you navigate IRB [Institutional Review Board] requirements for complicated real-world research designs. I had a two-day-long training on how to store private data securely. I had experienced survey designers look over my design in minute detail. Having this sort of support was crucial in being able to get a big project off the ground.” For other kinds of government partnerships, researchers might need specific legal expertise to write data sharing agreements or IT resources for handling sensitive data files securely. Chandrasekaran is now developing a proposal for an SSRC research network that would support less-resourced campuses to cost-effectively develop this kind of research administration infrastructure.

As an example of the potential for such relationships, Chandrasekaran points to federally funded Head Start programs that provide early childhood education and support to families. Those programs were evaluated by researchers using randomized evaluations, and the cognitive and developmental benefits they found helped support the case that they were a good use of public resources. Now, those programs have been expanded to reach hundreds of thousands of children around the country. “Head Start was based on evidence, and it is still generating data. Researchers are figuring out for whom it works best and under what circumstances, and that’s just one program.” For Chandrasekaran, making it easier for more experts at different universities to form community research partnerships is an opportunity for meaningful change: “Think about all the great universities out there, including minority-serving and emerging research institutions. It’s not far-fetched to say that in the next ten years, working with universities like those to build out their infrastructure could have a giant policy impact.”