Achieving Government Efficiency Requires More, Not Less, Investment

In this President’s Desk post, cross-posted from the Good Science Project, SSRC President Anna Harvey reflects on the meaning of “government efficiency” and better and worse strategies to increase government efficiency.

“Without an efficient government our Independence will cease to be a blessing.”

Joel Barlow, Oration, July 4, 1787

What Does “Government Efficiency” Mean?

According to the OED, the word “efficient” is derived from the Latin verb efficere, to cause or bring about. When the word first appeared in the English language in 1398, in a translation of the medieval Latin encyclopedia De Proprietatibus Rerum, it was somewhat redundantly appended to the word “cause” as “the cause efficient,” meaning the effective cause.

The OED records the first appearance of the word “efficient” in the context of government in a July 4, 1787 oration by one Joel Barlow, who warned his Hartford audience, “Without an efficient government our Independence will cease to be a blessing.” Barlow was still using the word “efficient” to mean effective. Amid considerable uncertainty about the outcome of the still-ongoing Constitutional Convention, Barlow exhorted his listeners to embrace an effective (“efficient”) national government: “Unite in a permanent foederal government, put your commerce upon a respectable footing; your arts and manufactures, your population, your wealth and glory will increase” (Joel Barlow, Oration, July 4, 1787).

As the Industrial Revolution sparked interest in manufacturing processes, the word “efficient” took on an additional meaning of causing or effecting more of some output for every unit of input: “The efficiency of an engine is the proportion which the energy permanently transformed to a useful form by it bears to the whole energy communicated to the working substance” (William Rankine, Outlines of the Science of Energetics, 1855). A more efficient machine produces more output for each unit of energy input. In the context of the efficiency of organizations, including governments, this version of efficiency was translated as “output per unit cost of the resources employed” (Arthur Seldon and F.G. Pennance, Everyman’s Dictionary of Economics, 1965). A more efficient organization produces more units of output for each unit of cost. A more efficient government produces more public goods and services (health, education, safety, infrastructure, etc.) for each dollar of public funds spent.

Government efficiency doesn’t mean that the government does less. It means that the government does more for every dollar it spends.

Investing in R&D Increases Efficiency

In industry settings, increases in efficiency have been achieved by investing in R&D. We have faster and more powerful microchips because we invested in the scientific research that has unlocked massive increases in chip productivity. We have faster and more powerful AI models because we invested in the scientific research that has enabled better predictions for less computational effort. We have more effective and less expensive treatments for disease because we have invested in the scientific research necessary to find, test, and manufacture those treatments.

[As an aside, as others have documented, our best estimates of the ROI on scientific research suggest that these returns are sufficiently high that we should be increasing, not decreasing, public investments in basic and applied science.]

Achieving increases in government efficiency also requires R&D. To increase government efficiency we need to know, is there some alternative way of delivering some public service such that we get more social value for each public dollar we spend? For example, is there a way to improve student outcomes for each dollar we spend on public education? Is there a way to improve patient outcomes for each dollar we spend on public health care? The answers to these questions aren’t obvious, and there are plenty of examples of policies that seemed like good ideas actually moving outcomes in the wrong direction (e.g., policies that prevent employers from asking about criminal records on initial job applications increasing racial discrimination against applicants).

To find more efficient ways of delivering public goods and services, we need to answer questions like, what produces more economic opportunity for residents of public housing per dollar of public investment: remaining in public housing, receiving unrestricted housing vouchers, or receiving “mobility vouchers” requiring a move to a lower-poverty neighborhood? What produces better learning outcomes for students in public schools per dollar of public investment: high-intensity tutoring delivered by humans or high-intensity tutoring delivered by humans plus technology?

There are answers to these questions. But we have to pay to see them.

We Underinvest in Government Efficiency R&D

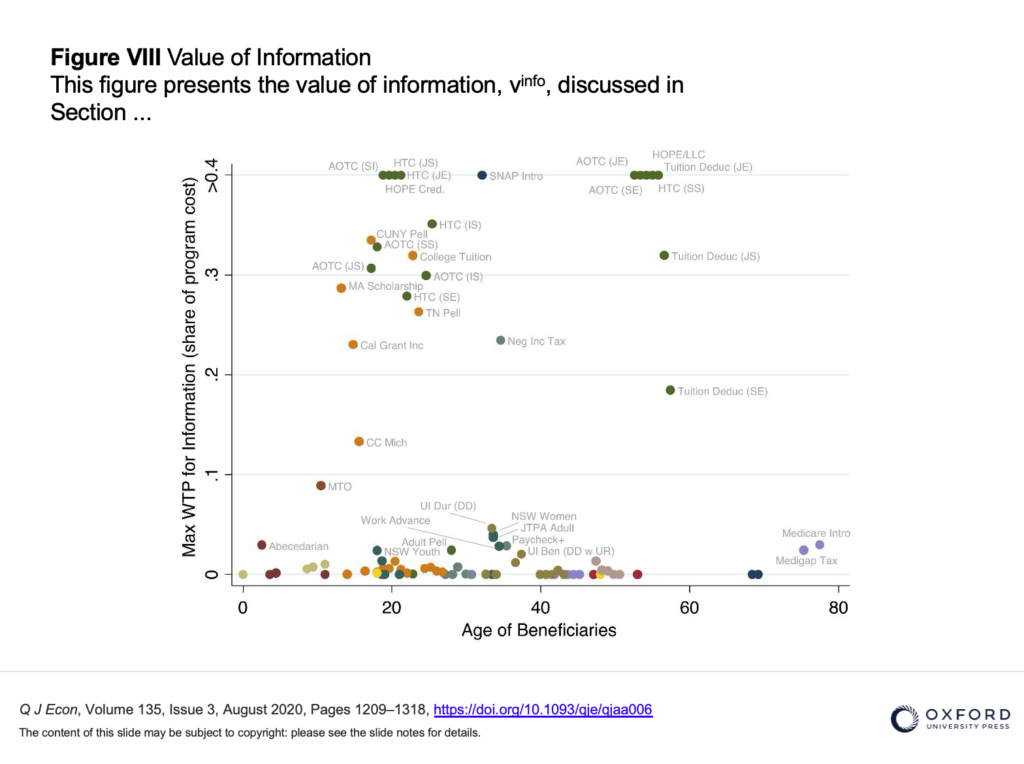

Given the potentially large returns to allocating public funds to more efficient programs, we can back out the return on investing in new research to learn more about the cost-effectiveness of public policies and programs. These returns are larger when we are uncertain about the net social returns to investing in alternative policies (which probably applies to most policy choices). For example, Nathan Hendren and Benjamin Sprung-Keyser have estimated the share of our policy budget that we should be willing to allocate to R&D to learn more about the returns to various policies. As you can see in the figure below, for many policies this share is larger than 40%!

Of course, we spend nowhere near 40% of our policy budget on program and policy evaluation research. At the federal level, although the Foundations of Evidence-Based Policymaking Act directed agencies to begin to evaluate their policies and programs, no funds were allocated for this effort. The NIH recently asked the research community for help in evaluating the impacts of its grants on outcomes, but is providing no funding for this work. At the state and local level, few agencies are investing in rigorous evaluations of the cost-effectiveness of their policies and programs.

Investing in Government Efficiency R&D

If we really want to increase government efficiency, we need to invest in government efficiency R&D. There are lots of different ways we could do this. For example, we could fund a new program at the NSF to support government efficiency R&D. We could increase the budget for the Office of Evaluation Sciences in the General Services Administration. We could appropriate federal funds to establish policy labs in every state to help state and local agencies evaluate the cost-effectiveness of their policies and programs.

What all of these strategies have in common is that they all require more, not less, government spending, at least in the short term. Even in the long term we might end up spending more, not less, on public goods and services. We might find programs that we would want to discontinue because they don’t produce enough social value to justify the cost. But we might also find programs that we would want to expand because they produce such large social returns! For example, the introduction of the Food Stamps program in the 1960s has been estimated to have produced $62 of social value for each additional $1 invested in the program.

Other programs providing health care and education for children have similar social returns. In-person visits to firms by IRS Revenue Officers increase tax compliance at an ROI of approximately 96x the cost of the visits, a much larger return than that from sending enforcement letters. Maybe we should be spending more on social benefit programs for children and IRS personnel, not less!

At the end of the day, a more efficient government might spend more or less than it spends today. But right now, we don’t know which programs we should cut, and which programs we should expand. If our goal is really a government that does more for every dollar spent, and not a government that just does less, we’re going to have to spend the money and do the work to find the programs and policies that produce more of what voters want for fewer public dollars.

It would certainly be easier if we could achieve government efficiency simply by cutting government spending. But thinking that government efficiency can be achieved just by reducing public spending is like thinking that we can make cars more efficient just by giving them less gas. Filling your car’s gas tank only half full won’t make your car any more efficient. It just makes it less useful.